This post is also available in:  Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German)

A morning on the bridge

After breakfast, Robert asks if he could change my sheets and clean my room at 10:00. Therefore I plan to spend the late morning at the bow of the ship.

But when I go up to check out, it rains. I decide to stay on up on the bridge. The Captain has laid out a few books on birds and marine life. I’m looking for “my” whale, which I’ve seen twice before, which is about twice the size of a dolphin, and where the dorsal fin is very far back on the back. I don’t find it. Also, with the sharks, there is no such fish. But the books are about animals of southern Africa. Maybe my whale does not occur in the southern hemisphere. That has to wait until I can go online again.

[Addendum: “My” whales have been minke whales.]

The sea is never dull.

On a day like today, with clouds and rain, it continually changes in the play of light and shadow. The wind is a little stronger and comes from the front. There are small waves with foam.

As it rains, a rainbow spans the ocean. There is nothing that hinders the view – I can see the whole semicircle floating above the water.

I spend the morning on the bridge, looking at the sea and the clouds or browsing through the field guides. I often stand on one of the balconies. There are small shade roofs and, because the wind blows, it is cooler there than on the bridge.

A bird flies over the waves. It’s a bird, not a flying fish because flying fish only manage a few hundred meters. I get one of the binoculars lying around on the bridge. The bird is gone.

hen, a few hundred metres in front of us, on the starboard side, I notice a large white spray spot. It’s not a wave; it’s something else. I lift my binoculars to take a closer look at the white spot and just as I am looking through, a colossal whale jumps vertically out of the water. His whole body floats in the air. Then he falls back into the sea with a big splash!

The animal is gigantic! Excitedly I tell the Third Officer who is on duty on the bridge. His first grip goes to the phone. The Captain has issued a most official order that he must be informed immediately of such sightings.

Then the Third Officer also takes binoculars, and we both look. The whale jumps again, another time we see the fluke.

Eventually, our ship comes too close to the animal. The whale no longer jumps out of the water. From time to time, we see the back and the blow.

The Captain and his wife come onto the bridge. He is armed with a camera and his large telephoto lens. I also have my camera with a telephoto lens with me and at least want to photograph the blow, but that’s very difficult. The ship moves forward, the whale in another direction. That makes aiming impossible. By the time I have the blow in the viewfinder, the magic is gone. Nevertheless, I managed to take a single photo that shows the back of the whale and its blow.

Never mind. Experiencing and remembering such an animal is more important than documenting such an event. I saw a giant whale that jumped vertically out of the water and fell back into the ocean with a big splash.

Equator

I know now how garbage gets into the ocean. Sailors throw it overboard. Of course, there are much worse offenders than our crew, but they do their part.

While I stand on the balcony of the bridge waiting for us to reach the equator, I see garbage being thrown overboard. First I can’t tell who it is, then I observe the man: It’s the Bosun himself. Splash – something that sinks quickly. Splash – a ratchet ribbon that still floats on the waves for a while. He’s about to bundle up white material when he sees that I see him. He pauses and goes to the other side of the ship.

Later I tell Pierre about it. He says that they were probably heavy things, like steel. That goes down immediately. And on the seabed, nothing and nobody cares. So says Pierre, who was upset yesterday about the hikers in the Alps, carrying full cans in their backpacks and then dropping empty cans on the wayside.

I’d accept pieces of steel and even wood being thrown overboard. They come from nature and can return to nature.

There were heavy things among them, but also old ratchets tapes made of orange nylon. And plastic parts.

Some people can ignore garbage in the ocean as long as it sinks. Weighty trash in the sea doesn’t bother them if they want to take beautiful pictures.

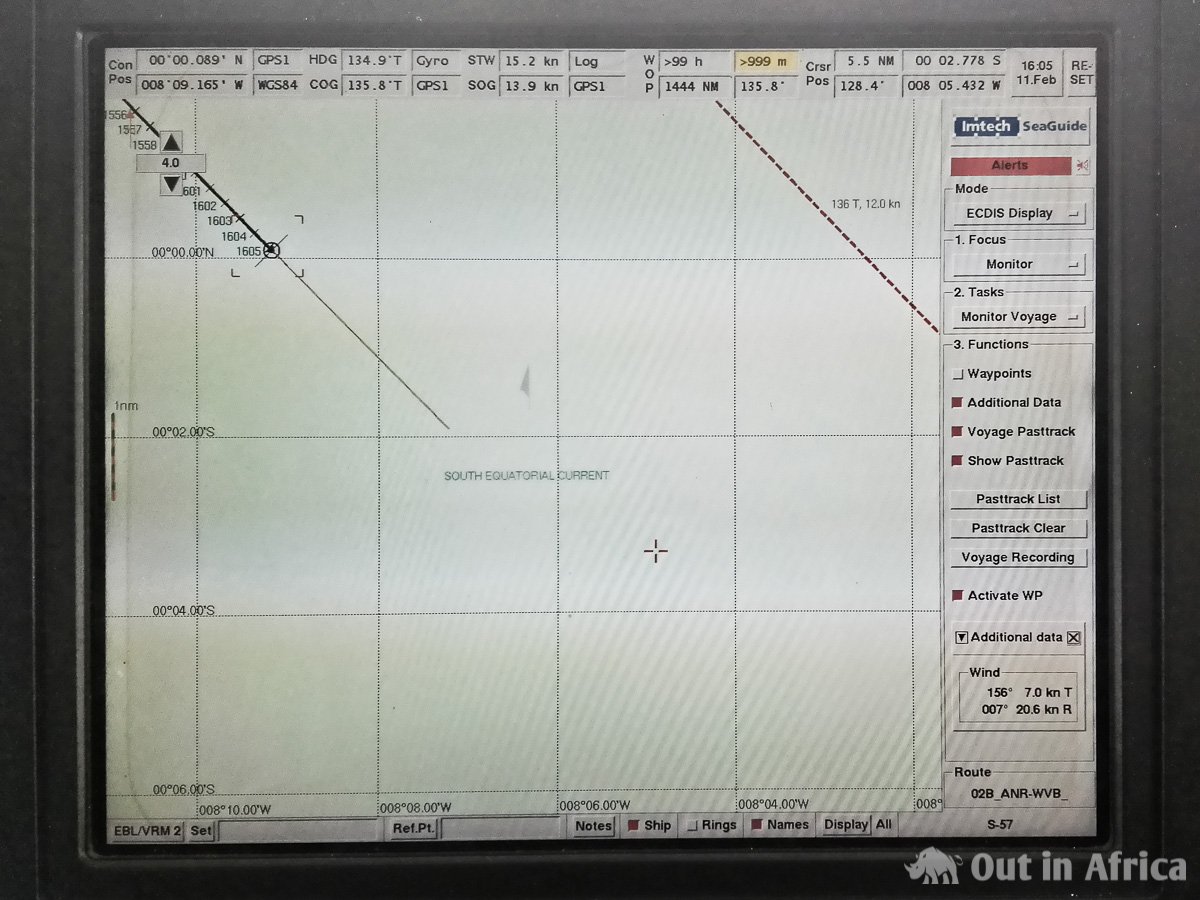

Then it’s time. We follow our course excitedly on the navigation device. We reach the equator.

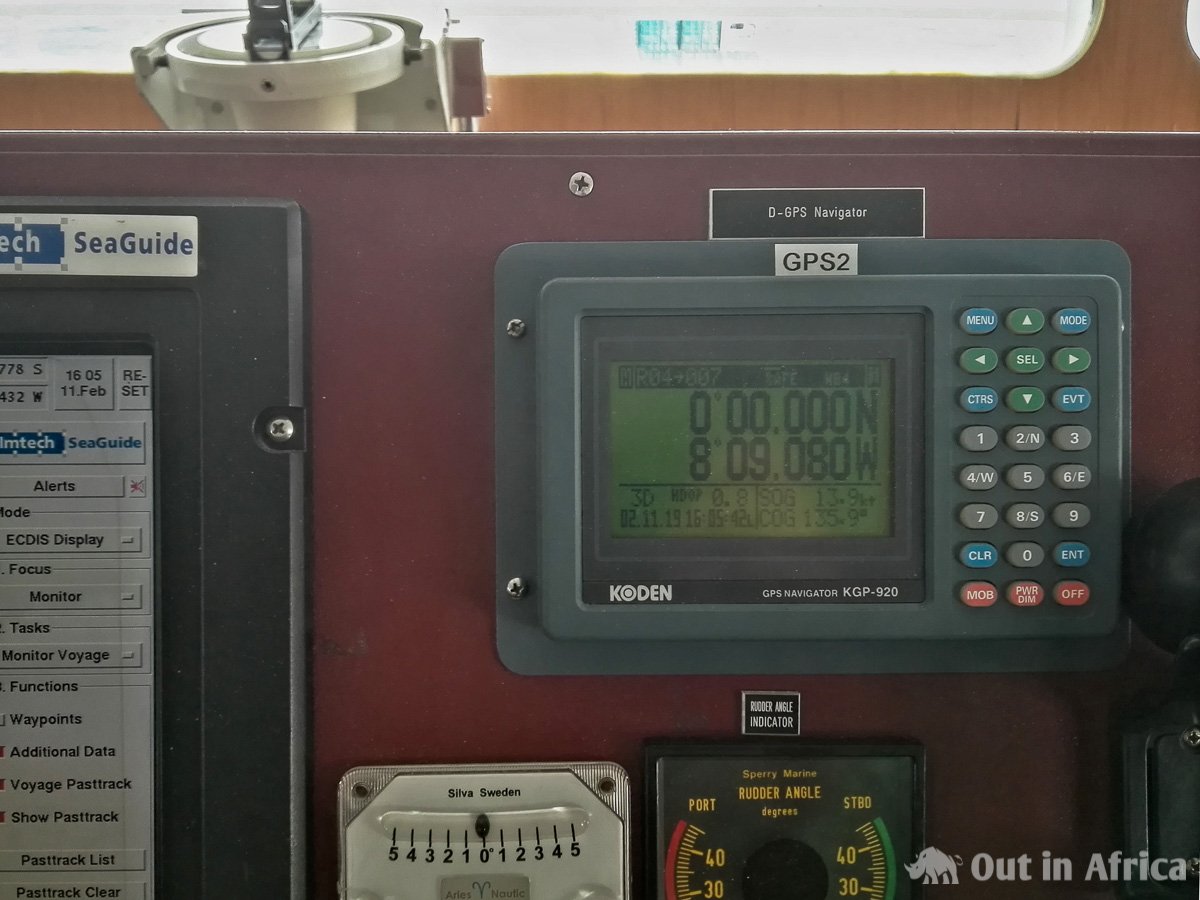

We cross the equator at 16:05:42. I can pinpoint that because I took a picture of the ship’s GPS. It shows 0°00.000 N 8°09.080 W.

Earlier the Captain had told us that there would be no bump when we are on the equator. Nevertheless, he and his wife are also on the bridge as all the numbers of latitude show a zero.

The sea south of the equator looks precisely the same as it does north. Today it is a beautiful deep blue.

Pierre and I stand on the bridge for a while and watch as we drive further south. He wants to show me something on the navigation device and bends forward. The Chief Officer, who is on duty at the moment, speaks sharply to him. We should stay away from the instruments! If we touch a lever, it could have disastrous consequences. And we are only permitted on the bridge because the Captain allowed it. We would not be allowed to do that on a passenger ship, and if it were up to him, the bridge would be off-limits for us.

Oops!

The Chief Officer is the second-highest rank on board after the Captain. He is a young, lean man with colourfully tattooed arms, blond and he has a slight overbite. I have watched him for a while, and know that one day he wants to become Captain. He is a responsible young man who works hard. But he still needs a few soft skills to become a captain, and I hope he learns them before he reaches that rank.

Usually, he’s alone on the bridge during his afternoon shift. Maybe the many passengers (Pierre, the Captain’s wife and me) annoyed him during the crossing of the equator.

Pierre and I look embarrassed, say that we understand about the instruments, acknowledge that it could have harmful consequences if we touched anything and that we are sorry.

We’re not going to argue at all. He is right. Only his way and his tone are offensive.

We check out. We want to go forward, to the bow of the ship. He doesn’t want to let us go there. Work is being done on the vessel, and something bulky could fall on our heads. We promise to take good care.

On the way to the bow, we don’t meet a single working sailor.

I ask Pierre if he touched a lever or something. No, he just bent forward because he could then read the navigation device without glasses.

I’m considering whether it would be so easy to put the ship in danger. There must be safety mechanisms in place to prevent the worst from happening if someone stumbles in heavy seas and accidentally pulls a lever. Pierre thinks that if you were to operate the ballast levers, something could happen – but not necessarily a catastrophe, especially if something is done about it immediately. But he wasn’t that close to the ballast lever. However, the lever could only be operated if the ship was steered in manual mode. We’ve been on autopilot for days.

Never mind, now we are standing on the bow and observing flying fish again. Then Pierre goes to celebrate his aperitif before dinner.

As soon as he’s gone, a big bird flies by. I manage to take a photo. It is not particularly beautiful, but rather a proof photo. No, no proof photo in case Pierre once again says that there could be no birds here, but a proof photo for me. Later I identify the bird as a Great Shearwater. It is another entry on my life list of seen birds.

Thunderstorm

It’s just before 20:00. I have, like every evening, a date with the sunset and go up to the bridge balcony on the starboard side.

A huge thundercloud comes from the front, from the south. A thick curtain of rain falls out of it. The horizon disappears behind the storm.

A strong wind precedes the thunderstorm. It whirls up the sea. The waves now have white foam on them.

In the west, it is still bright. The setting sun is an orange ball in the sky. It makes the sea shine coppery.

We pass through a left offshoot of the thunderstorm. Heavy drops fall. I am standing under the roof of the bridge balcony. Still, the wind from the front is so strong that the raindrops fly almost horizontally.

I sincerely hope that Panasonic will keep its promise that the camera is splash-proof because I want to witness this spectacle of nature. I don’t care that I get wet. It’s as warm as in a laundry room.

The storm cloud and the rain that falls from it passes us and pushes itself in front of the sun. Now the rain glows orange. The shadow that the cloud casts on the sea is dark, almost black grey.

A little further south is another raining thundercloud. Its rain is blue-grey.

Also on the north side, a thundercloud rains down in dark grey.

I hear thunder rumbling in the clouds, but I don’t see any lightning.

It’s a tremendous natural spectacle.

I feel very much alive in this meeting of clouds, rain, sea and the orange light of the sun behind it all.

I don’t see the sun – the rain is too heavy. But it has to go down slowly because the orange rain is getting darker and greyer.

The Chief Officer, whom I see through the window on the bridge, is leafing through some papers. He notices nothing of what’s happening out here. Or it’s just routine for him. Sunsets doesn’t interest him.

I feel sorry for him.

Would you like to see an overview of all articles about my journey on the cargo ship Bright Sky? Click here for a table of contents.

Leave a Reply