This post is also available in:  Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German)

My brain has become accustomed to the swell and the rolling of the ship. Today I feel hardly any nausea. I even looked at the waves to see if they were less high, but I would say they were still at three to four metres. Only the wind is not so strong anymore.

When I sleep, especially when I sleep on the side, as I like to do, the swinging from right to left is annoying. When the ship goes into its most inclined position, the body rolls with it. But when I lie on my back, I hardly notice the effect.

The sunrise is beautiful today. A few clouds are shining in orange and pink. Where the light reflects on the water, it is as if golden flakes float on the sea. I stand for a while on the balcony of the bridge and take pictures.

The ship is steered by autopilot, but that doesn’t mean that the crew doesn’t have to watch out on the bridge. As we approach the coast, we occasionally meet small Spanish fishing boats that cross the freighter highway. At night it is particularly dangerous because these boats are not illuminated and can only be seen by us on the radar. The small ships probably have no radar to sight us, or they trust us to see them and not run them over. Most of the Bright Sky is dark at night. Anyway – no matter if the fishermen see us or not – they don’t change their course. The crew on the bridge has to do that.

The task of the bridge crew is, therefore, to observe the radar screen and avoid any obstacles. During the day they examine each ship they see on the radar with binoculars.

After sunrise, when the gold flakes on the water turn silver, I tell the crew on the bridge that I want to go to the bow of the ship. If the weather is terrible, the officer on duty can veto an excursion for safety reasons. I also have to inform the bridge when I return. This is not exaggerated control, but a simple safety routine.

The big waves splashed up to the upper deck. From the waterline to the upper deck, it is at least 4.60 m, and it shows that the waves are still quite high. From the upper deck, I can also estimate the height of the waves much more easily, because I am more at their height than 12 m above them. But it is still relatively dry.

I walk past all the cargo holds. Their sidewalls protrude more than two meters above the upper deck.

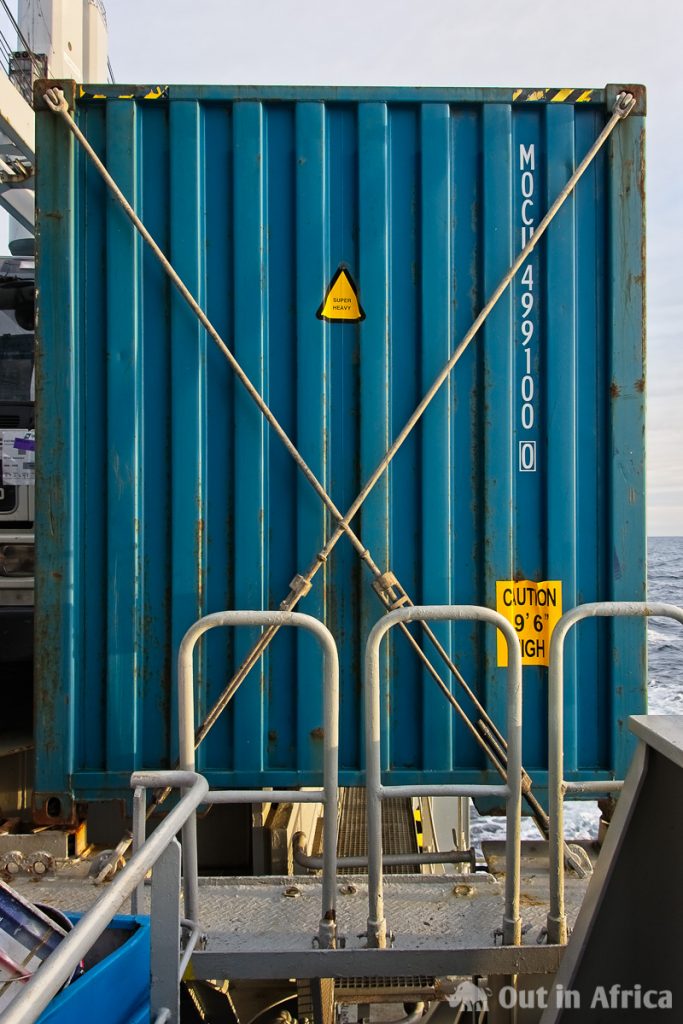

Either containers or trucks are loaded on the front cargo holds. Since we also want to have a container transported to Namibia, I pay attention to how they are secured. There are the safety mechanisms, which are attached at the top of the four corners of the containers before another one is put on top. They can be fastened or released with a lever.

Then containers are secured with diagonally running rods to the containers below or eyelets on the deck. This is only done here for the bottom two layers. Above this, there is only a diagonal bar which connects the last two containers in a row – i.e. on the far right and far left – to the container below. Otherwise, only the corner securing device is responsible for fastening the containers. Pierre, however, thinks that this will hold. The containers that are not secured with bars are empty cooling containers, i.e. very light containers. So far, it has held up, and the weather is only supposed to get better.

In one container, it’s banging very loud. I can hear it up to my cabin when the window is open. I don’t know what’s going on inside. Maybe the cargo wasn’t secured well enough.

The light from one of the trucks on the front cargo holds is still on.

At the very front, at the head of the ship, there are two decks. On the lower deck are the anchor and rope winches. It is open to the vessel but closed to the sides except for a few slots. In this way, the seamen who have to work there have a sheltered area. Above is another deck, which can be reached by a ladder. But the hatch to the top is still closed. The captain wants to have it opened as soon as the weather improves. Then it is possible to go to the extreme tip of the ship and fly like Leo and Kate on the Titanic.

It is tranquil in front. I cannot hear the ship’s engine can anymore. Only the sound of the waves when they are cut up by the vessel is audible.

Back in my cabin, I make coffee and tea for the day. My thermo cup for coffee and my thermos jug for tea is worth its weight in gold. But they have to be unbreakable. They tip over too quickly when ship sways.

Robert comes by and empties the garbage can. He also gives me a paste in a water-soluble plastic coat. I have to put the whole thing into the toilet. After five minutes, everything has dissolved and is flushed away. Then there is another bottle with a liquid, from which I should give each week a little bit into the toilet. This serves the biological treatment. Then there is another bottle with a liquid, of which I should do a little bit into the toilet bowl every week. This serves the biological decomposition of that which is generally flushed down the toilet.

The toilets … They are a mixture of a toilet as we know it and an aeroplane toilet. I.e. if you pull the trigger, everything in the bowl is vacuum-sucked to somewhere else. But then a little water flows in.

For lunch, Pierre treats me to a glass of KWV Shiraz. As a winegrower and wine connoisseur, his judgement is “very good for such a cheap wine” and “just the right thing for lunch”.

In the meantime, we have passed the Bay of Biscay and are on N43° 56.404′ W10° 09.501′, about 115 km northwest of the next tip on the Spanish mainland. Soon we will change course to more to the south. In this way, we will bypass Spain and Portugal. The next landmark we will see will be the Canary Islands.

In the evening I have to think of the people who asked me before I left:

“Won’t you be bored?”

What an absurd question!

Why should I be bored?

There is so much to do!

I’m curious. I want to know. Here on the ship, I often find myself wanting to open the browser and google something. That doesn’t work. Or to be more precise: it works, but it costs. That’s why I have to find other ways to get answers to my questions. Either I ask someone who might know – Pierre or the captain are good candidates. Or I have to investigate it myself, as with the question of what high seas do to the body. The answer is: you get seasick, but at some point (in my case after 24 hours) the brain can deal with the constant fluctuations in the earth’s gravitational pull and the recurring shifts from above and below. Then the seasickness is gone.

Then I follow my creativity and take photographs, edit photos and write. I learn a new program for image editing. Before I left, I loaded YouTube videos onto my computer and now watch them one by one. In between, I practice what I have learned.

Whenever I want to relax, I keep reading Scott Kelly’s book.

And then there’s the experience. Life here on the Bright Sky is simple. There is the sea, the sky and the ship and of course the people on the ship. Most of the crew I don’t see at all.

If I leave the crew out, the ship, the sky and the sea remain. And if I limit it to sky and sea, I already have a lot to experience. The sky and the sea change always, just as the sun moves over the sky and the light changes. The colour of the sea has changed as well. We are no longer on the North Sea, but on the Atlantic, more than 100 km away from the next land. The sea is deeper; it’s colour darker.

So I don’t need animation or fun, no television, no distraction. I don’t have time for all that.

The sunset is not spectacular today. There are clouds, but they tend to cover the sun rather than let it illuminate them. Up, on the bridge, there is also a strong, cold wind.

It is night. We are currently at N41° 52.439′ W11° 01.811′, 177 km from the mainland.

Now the Bright Sky is alone on the ocean. I have seen only one ship or rather the mast on the horizon. The seagulls that accompanied us at the beginning are no longer there. We are too far away from the mainland.

Would you like to see an overview of all articles about my journey on the cargo ship Bright Sky? Click here for a table of contents.

Leave a Reply