This post is also available in:  Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German)

An ode to crane operators and dock workers

The timetable has shifted backwards because of the trucks on which trucks are loaded, on which cars are loaded. It is challenging to hoist them by crane onto the ship and secure them. Instead of 14:00, departure will be at 20:00.

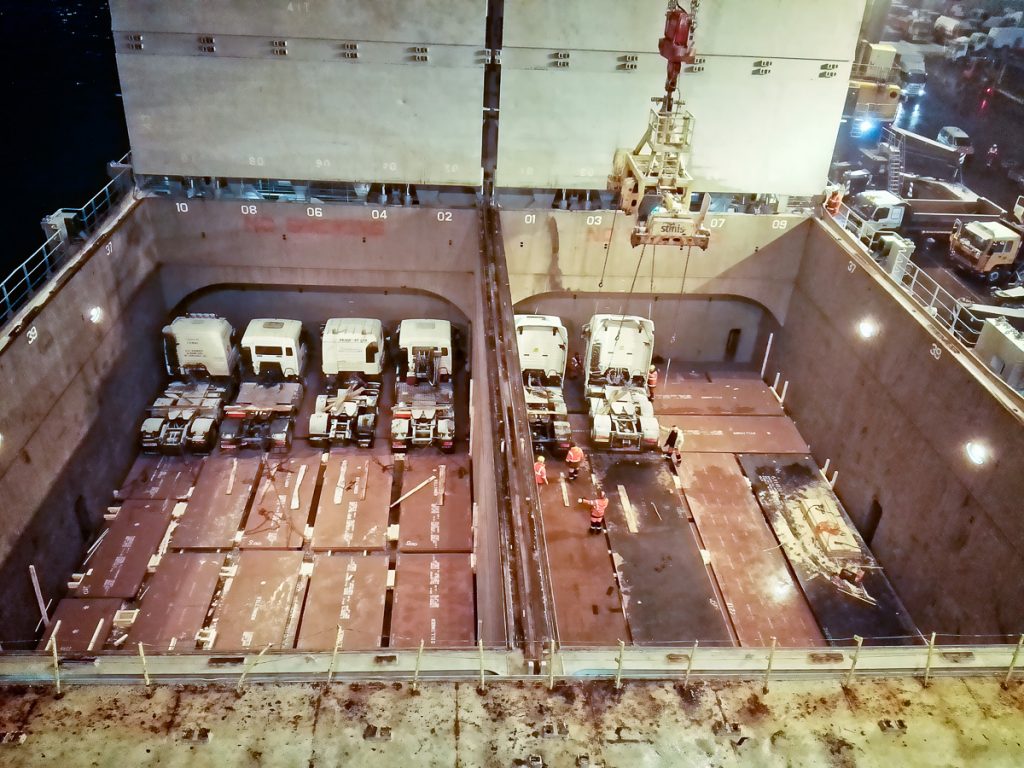

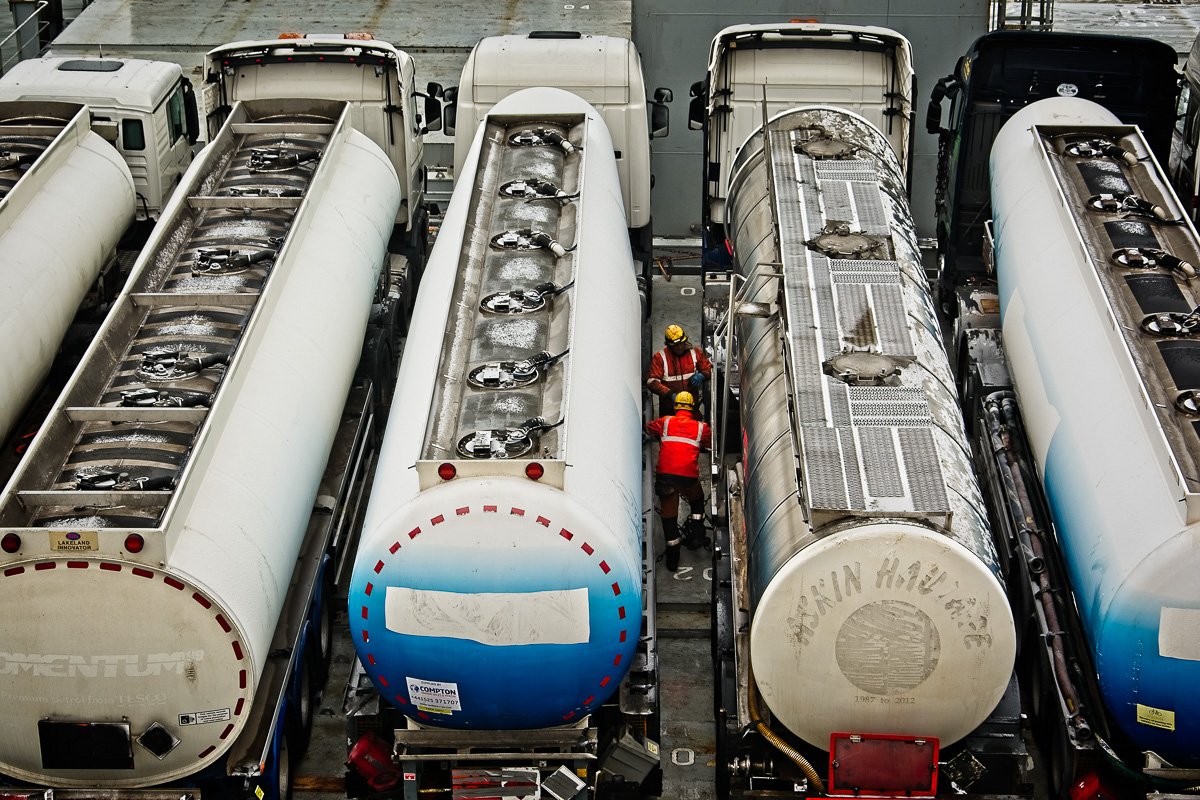

I look out of the window at 7:00. Outside extraordinary things (for me) happen: Trucks are mounted on the steel plates in the cargo hold: real, big trucks and the corresponding tanks or other trailers. The crane operators in this port earn my utmost respect. Safe and accurate to the centimetre, they can bring a truck from the quay to the cargo hold without bumping into or scratching anything. Even the last few millimetres down are well controlled. The vehicle is set down very gently. The shock absorbers on the vehicles hardly kneel at all.

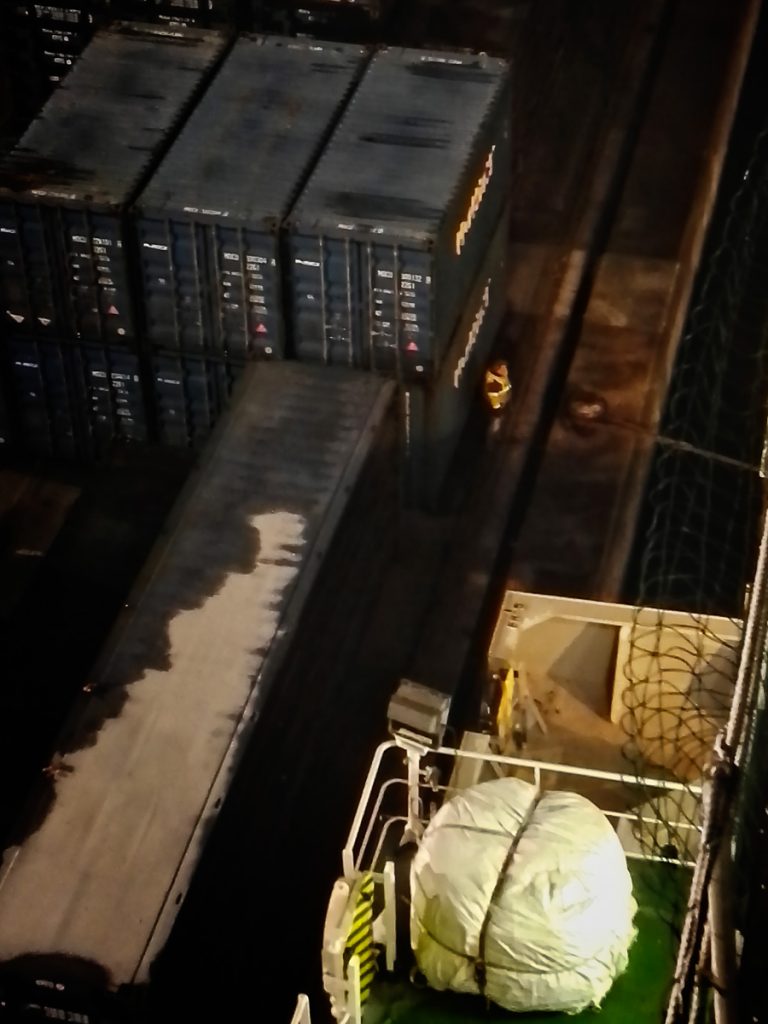

The front cargo holds were already closed at night. The crane places one container after the other on top, three or four layers high.

In the morning I go to the balcony of the bridge. Outside there is snow, and it is quite slippery. I watch the hustle and bustle on the dock.

A crane is always at the centre of all loading operations. It is the dancing giant that weighs 439 t and can lift and lower up to 144 t at a speed of 120 m/min (as the website of Liebherr, the manufacturer, informs me). The crane stands on a substructure with 80 wheels with truck tyres, giving the crane mobility in all directions. The wheels are not, as we know from cars, mounted on axles transversely under the base of the crane, but in groups of four wheels mounted on the bottom so that each group can move in all directions – similar to the wheels on a shopping trolley from Aldi or Rewe. In this way, unlike a car, the crane can move in all directions: forwards and backwards, to the side or diagonally. Ten groups of four are mounted on each side of the crane.

When the crane has to do its job, it is firmly supported on the dock by an X-shaped support base.

A crane of this type is used in many different ways: from containers to heavy loads and bulk goods, can be moved with it. Sophisticated technology enables the crane operator to transport and set down his loads vibration-free.

Near the crane, there is a small yellow cubicle that serves as a shelter for the dockworkers while they wait for their colleagues on board to clear the crane of its load. Now that we have temperatures around freezing point, the workers have lit a fire in an oil barrel with holes for better ventilation. The men burn old planks in it. They often stand by the barrel, usually only for a few seconds to warm themselves.

For each crane, there are two teams of men: The crew on the dock attaches trucks to the crane. Next, the crane operator lifts the truck onto the ship and sets it down accurately. On the ship, there is a man who signals the crane operator by hand signal or radio whether he should swing forwards or backwards, or right or left.

When the truck is at its intended position, the second team on the ship releases the brackets and immediately begins to secure the vehicle with thick chains. Meanwhile, the crane operator steers his equipment back to the dock, and the next round can begin.

With containers, you don’t need a team on the dock. The crane operator can engage the gripper himself. On our ship, containers are still connected in the old way: Harbour workers attach safety mechanisms to the top of container corners. Then another container is raised at the top, and the safety mechanism engages. The dockworkers do not have to climb up the containers at all. Once they have provided a layer of containers with the devices, the crane takes them up to the next layer, which it has now begun to stack.

Next, the containers are connected with diagonal bars to the container underneath. However, this is only possible for the lowest layers. If the containers are stacked more than two layers, the bars are no longer used.

There is, of course, an extended logistics system involved in loading by crane. The goods to be loaded must be brought to the dock. The trucks are driven under the crane. Containers and other freight are transported by forklifts of all sizes or by truck.

The whole operation is like a complicated dance within a 500 m radius of the ship. Everything is always in motion. Except during coffee breaks, and when changing shifts, there is never a standstill. Work is done around the clock, even on weekends, day and night, in three shifts.

In the morning, the cargo hold in front of my window is packed, and the hatch is closed. Then more trucks are hoisted on top and carefully fixed with chains. For lunch, the dockworkers have finished. The crane leaves our dock with loud beeps. A forklift truck with the harbour workers’ shelter and another with the corresponding fire barrel followed in tow.

Now, after lunch, there are only one of the three cranes left with us. It loads containers onto the penultimate cargo hold.

After the loading, another team of men is checking the load securement. Are the chains that attach the trucks to the ship tight? Is the container safety catch engaged? Nothing should slip in heavy seas.

The seamen are involved on the sidelines with all the loading. They open the cargo hold doors and assist the dockworkers when necessary. However, the crew can also unload and load the vessel. In smaller ports, they often have to bring cargo to and from the ship with the ship’s cranes. Here, in Antwerp, however, everything is entrusted to the port workers.

Yesterday the Chief Engineer came for breakfast with tiny eyes. He had hardly slept the night before because the company that delivers the fuel did so at 3:00 a.m. Bunkering diesel and oil is the Chief Engineer’s responsibility. The captain was irritated. It is not normal for fuel to be delivered in the middle of the night. Did someone want to take advantage of the seamen’s tiredness and cheat us? One possibility, for example, would be to fill the tanks with less fuel but to charge a full tank. The Chief Engineer had thought the same and had been vigilant. Everything had been done correctly.

The loading of the Bright Sky is completed at 15:30. The crane moves on its 80 wheels to another dock and another ship. Two forklift trucks pick up the yellow shelter and the fire barrel and drive behind the crane. It is by no means the end of the day for the dock workers. Here, with us, a pleasant peace has occurred.

The large area where everything that had to be stored on the ship was stored is almost empty. A truck-sized propeller and a few cable reels are still standing around. But they are destined for Valparaiso, Chile, not for southern Africa.

It is suddenly relaxed onboard, almost calm. The sailors haul a few things on board with a ship’s crane and lash others. I lie down on the bed and read on in Sean Kelly’s book.

When I think about the space traveller Sean Kelly, I have to think again about the Portuguese seafarers of a little more than 500 years ago. They looked for a way around Africa, always careful, always in fear of dragons behind the next horizon. They often returned because they did not dare to go further. But then the next seafarer came and went on. After Diego Cão, whose ship first reached the coast of Namibia, came Bartholomäus Diaz, who circumnavigated the southernmost point of Africa. After Diaz came Vasco da Gama, who finally reached India. Each explorer went further and thus extended the boundaries of knowledge of the world. Space travellers today are what the seafarers were then. They also extend the boundaries of knowledge to one day be able to travel to Mars and even further.

With this trip, I also follow the path that Portuguese sailors discovered many hundreds of years ago. Because they extended the limits of what was known and possible, I can now travel to Walvis Bay on the Bright Sky.

For dinner, we have an excellent pizza. For the first time in a week, the officers’ mess is full. Firstly there is pizza, and secondly, everyone now has time to eat something. The friendly cargo agent of MACS, his job done, says goodbye to us. I thank him for the interesting conversations, he as well.

I shower again at 19:30. On a swaying ship, I imagine, showering is undoubtedly not as easy and comfortable as in calm waters. Tomorrow we will head towards the English Channel, then into the Bay of Biscay, which is notorious for its storms. Today we talked about 4 m waves there.

Berendrechtsluis

I get to the bridge just before eight. The pilot is already on board. The Lines Men are standing at the bollards to release the ship’s lines. On the right balcony of the Bright Sky, the console with which the Chief Officer steers the vessel away from the quay wall is open. Pierre is already there.

Only one tug moors at the Bright Sky. More is not necessary, because the ship will not turn in the Churchilldok, but will drive back out and then only turn 90 degrees into the Schelde, to then drive straight ahead.

We’re leaving on time. Everything is quiet and calm. First, we leave the dock sideways. Then we go a few hundred meters, pulled backwards by the tug, then we are in the canal and drive slowly towards Berendrechtsluis.

With such a large ship the lock seems very narrow. But it is, according to the pilot, 68 m wide and 500 m long. The entrance is tricky because it lies directly behind an almost 90-degree curve. Already before the curve, the speed is throttled. The tug, which still accompanies us, brakes us by reversing with full power. We drive very slowly, but such a massive ship builds up a lot of momentum. Slowly, very slowly, we enter the lock. At one point I think we won’t be able to stop in time because we won’t stop. But then the Bright Sky stands still, and Lines Men moor us. The tug leaves us. A barge, the size of those who sail on the Rhine, follows us and fits in easily.

It takes perhaps a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes until the lock has lowered us by a few metres. Then we can go on.

Shortly afterwards, I leave the bridge. I say goodbye to all the WhatsApp groups that followed the departure and the entrance to the lock. Maybe there will be a mobile reception in the next few days, but perhaps not. If there is, I will contact them again, if not, they will have to wait until we reach the Canary Islands.

Would you like to see an overview of all articles about my journey on the cargo ship Bright Sky? Click here for a table of contents.

Leave a Reply