This post is also available in:  Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German)

The first thing I notice when I enter the engine room is that it’s not a room. It is a labyrinth of corridors, rooms, floors, stairs and machinery that takes the space of an apartment building.

The second thing I notice is that it is hot. The sailors have hung their washed overalls over a railing because they dry very quickly here. I am still at the beginning of our tour. The deeper we go into the labyrinth, the warmer it gets.

The ship is like a small town. Everything we need for propulsion and life must either be taken along or produced by us. It is not only about the propulsion, but also about the control, about electricity, about water supply, about sewerage, about good air from the air conditioning system. Emergencies must also be provided for, e.g. water must come out of the hydrant in the event of a fire.

The person responsible for all these things is the Chief Engineer. He has several colleagues who help him with his task. In the officers’ mess, I meet the Second and Third Engineer and the Chief Electrician at meals. Their work area is deep down in the ship, in an area called the engine room, but far more than that.

At breakfast, the Chief Engineer, Pierre and I agreed that we would meet for a tour after lunch. We wear sturdy shoes, no flip-flops. We are allowed to take pictures, but we should think of a wide-angle lens.

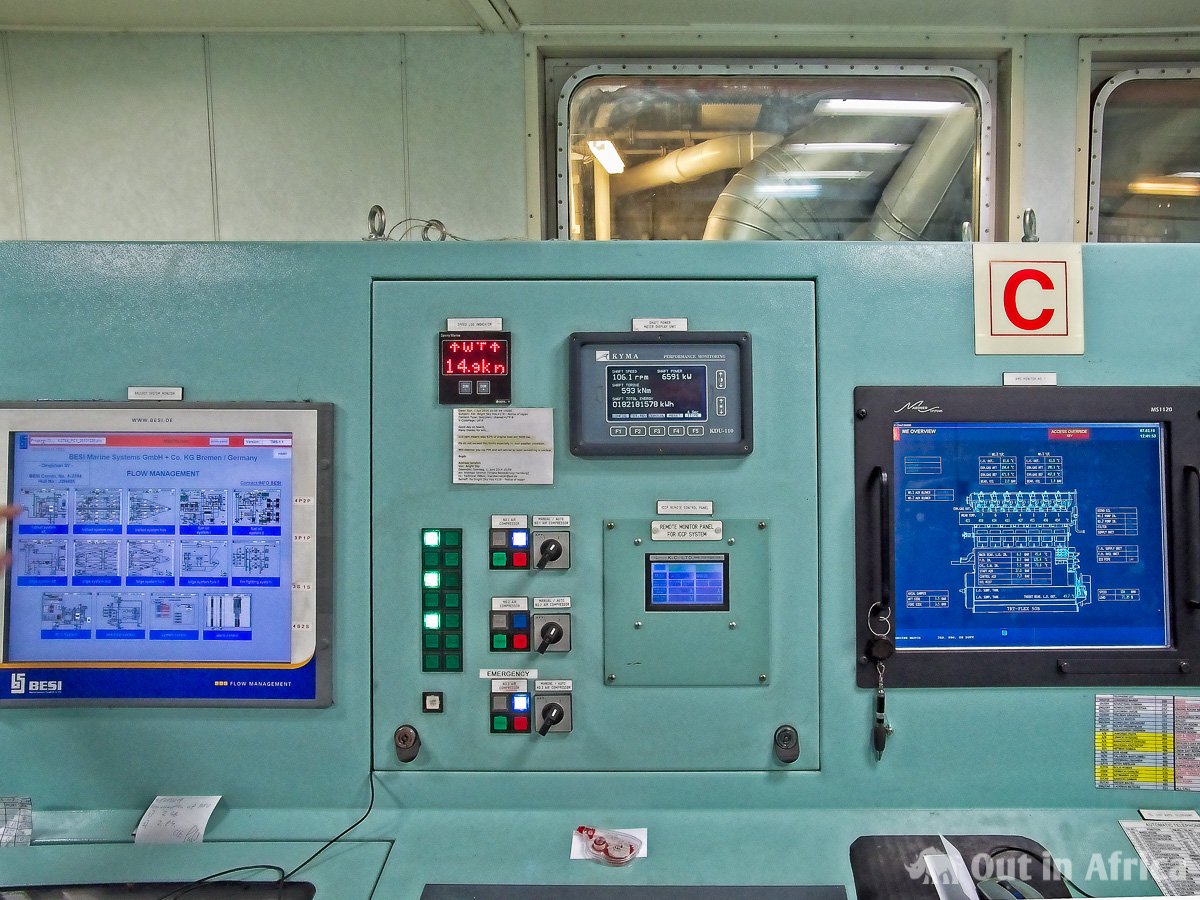

We go downstairs, past changing rooms and drying overalls into the brain of the ship. It is a computer centre where all the ship’s machinery is monitored: the engine of course, but also the generators, the fuel consumption, the temperature, the sewerage, the drinking water production, the air conditioning, etc. What we see in the car on the console above the steering wheel, is monitored here, in a room as big as a tennis court. The computers occupy several racks.

Just like the bridge, this control centre is staffed day and night.

We get earplugs pushed into our hands, put them into our ears and off we go. First, we pass through a large workshop with workbenches, machines and of course, tools that are neatly kept on the wall.

Then we go on into the kingdom of machines.

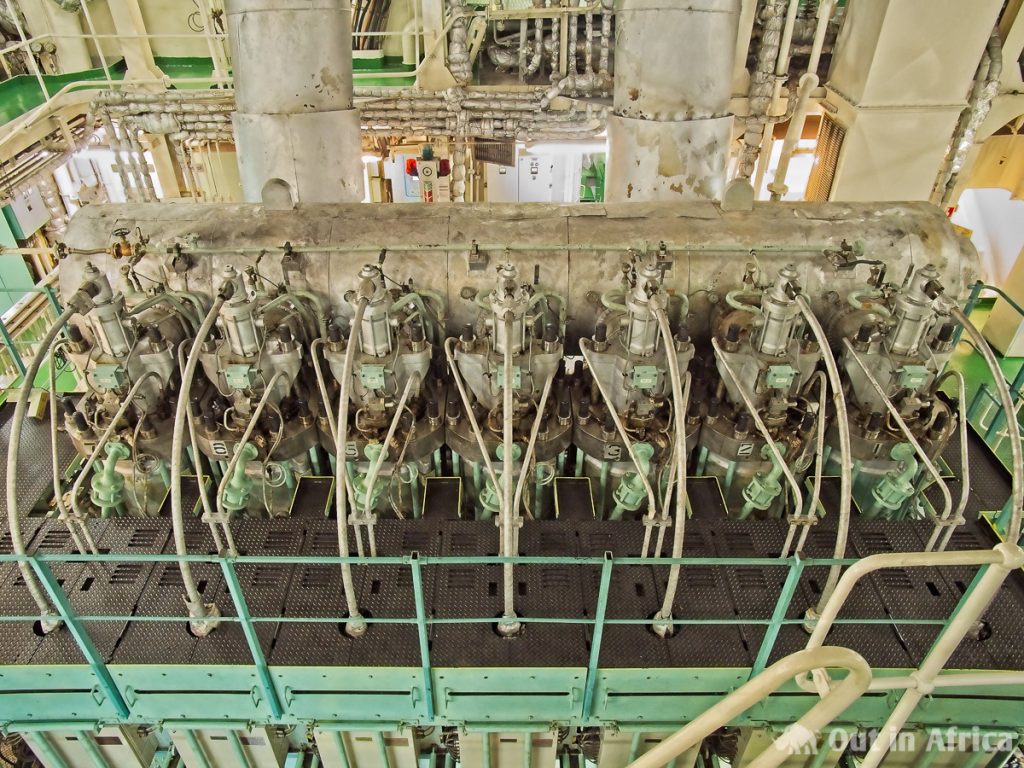

The engine that drives the ship is three stories high. It is impossible to see it as a whole, because, for easier maintenance, it is surrounded by a scaffolding that allows the engineers to reach every part.

We go deeper and deeper down the steel stairs. The stairs are steep but have a railing. The Chief Engineer shows me how to grip the railing to have a secure hold – not from above but from below.

The engine drives a large crankshaft at 105 rpm with the propeller at the end. The propeller is, of course outside, in the water. The diameter of the propeller is about the size of two storeys.

Before the oil that lubricates the engine can be used, it must be heated to over 126° C. Of course. It must also be cleaned. The cleaning is not done by oil filters, as in a car, but by centrifuges, which throw out the contaminants in the oil. If I have understood it correctly, the centrifuges are rinsed with water now and then to remove the contaminants. It was in this centrifuge, where the mishap with the non-closing valve happened in Hamburg, which caused water to enter the oil.

The drive is one thing: steering is another. The rudder, also outside in the water, is moved by a large hydraulic system.

We pass the exhaust. The air around it is glowing hot. To prevent the machinery from overheating, a cooling system is in place. Cold seawater is pumped through large pipes through several radiators. They cool the rooms down to more bearable temperatures.

Three large diesel generators provide electricity. They are not all in use at the same time. One is enough to provide enough power for daily consumption. When the cranes on the ship are used, a second generator is started. The third generator is redundant if one of the other two fails.

Drinking water is produced onboard by a desalination plant. Only during a more extended stay in a harbour is additional drinking water bunkered, as harbour water is too muddy. If I have understood it correctly, desalination works via distillation. There is enough heat so that it can be reused for this purpose.

Then there is the sewage system. A vacuum system sucks the dirty water from the toilets and showers. Compounds are added to the wastewater to accelerate biological degradation. In the end, it is drained into the sea. However, this disposal is strictly regulated and may only take place further than twelve nautical miles from a coast.

The engineers are well-trained people who must be able to carry out even major repairs far away from any help. What if a cylinder in the engine breaks down? Then it is replaced. A replacement cylinder stands next to it. So they need to know all the details of the engine, be able to logically analyse the processes to find the source of the problem and also have the necessary know-how to repair.

I am very impressed by this vast empire of machines and pipes and by the people who monitor and maintain everything.

After our excursion to the realm of engineers in the afternoon, we talk at dinner about the work of the officers on board: the Chief Officer, the Second and Third Officer and of course the Captain.

The reason for our conversation is an injury to a sailor in the afternoon. The wound was more substantial than that one could have stuck a plaster over it. He had to go to the hospital ward and the second officer, who is best trained for such cases, had to decide whether to suture the wound or not.

Pierre and I question the Captain about medical care on Bright Sky. No, there is no doctor on the ship, but there is more than a few ibuprofen and cough syrup on board. The Captain and the officers have to do training that covers much more than an ordinary first aid course. The hospital ward is well equipped with material and medicine, including prescription medication such as antibiotics. It may not be possible to perform operations, but everything is available for more severe cases. I even saw a defibrillator.

That is how we discuss the training of officers and their qualifications.

Our Captain tells us that he has a whole folder of papers that make him a captain. Many of them he has to refresh regularly. We haven’t come up with a job that requires more qualifications in such a wide variety of subjects. The Captain is not only the person who gives the orders on the bridge. He no longer has to determine the position with complicated instruments – that’s why we have GPS today – but he still has to know how to do it. In the end, however, he is a manager. He’s the head of the chief engineer and the chief officer. He is responsible for the ship, for the people on board and the goods being transported. The management is not an easy task. His official title is “Master”. He is at once the master of the ship as well as a master of his profession.

The Chief Officer and his two colleagues mainly work on the bridge. Even the ocean is not yet navigated autonomously. Theoretically, as soon as you are on the open sea, you can enter a few waypoints and no longer have to worry about steering the ship during the voyage. Practically this is not done, because the external circumstances can change. Especially on busy sea roads and near the coast, where fishing boats sail around without radar, it is the officers’ job to avoid collisions with other vehicles. Even at a slightly higher level, the officers have to reconsider the course again and again. If there had been a real storm in the Bay of Biscay, we would have waited somewhere in the English Channel until it was over. If the wind had come strongly from the west at the Canary Islands, we would not have crossed between Tenerife and Gran Canaria, but further east between Lanzarote and Fuerteventura on the one side and the African continent on the other side, because these two islands would have given us more protection. Thus, course changes are not fixed days before, but a few hours earlier. Even if nobody has to hold a steering wheel in their hands to steer a ship in the right direction anymore, there must always be someone on the bridge who monitors and watches everything.

The chief officer is also the superior of the ordinary sailors. He decides which work has to be done on board. I often see him, dressed in a red overall on deck, talking to the Bosun, the foreman of the sailors.

He is also responsible for the safety of the cargo. Already in Antwerp, I could observe how he checked everything when all was loaded. Were the chains that fixed the trucks on board tight enough? Were the security mechanisms of the containers engaged? In general, the cargo agent in the port will finalise the cargo planning together with the Chief Officer – long before the ship enters the port.

I already reported above that the Second Officer onboard the Bright Sky is the specialist for medical care. His officer colleagues also have the training, but if a wound has to be sutured, it’s the Second Officer who does the job.

The additional task of the third officer is safety (safety in the sense of “security” is the task of the chief officer). The Third Officer had already given us an introduction for emergencies in the port of Hamburg. He is responsible for the various security exercises such as “Abandon Ship” and “Man over Board”. He has to make sure that all lifeboats are in their place and he has to check the rescue suits of the entire crew regularly.

The people who dine with us here in the officers’ mess – the Captain, the officers and the engineers – are highly trained people who bear considerable responsibility. I became aware of this today with the Chief Engineer, who not only has to take care of the machinery but also all the other technology on board. I also notice this with the officers, who have to enter more than just a few commands into a computer.

In the evening, Pierre and I again go to the bow of the ship and take pictures of the sunset.

Would you like to see an overview of all articles about my journey on the cargo ship Bright Sky? Click here for a table of contents.

Leave a Reply